About the Artist

Roy Lichtenstein (1923 – 1997) was a defining voice of American Pop Art whose sharp wit, immaculate surfaces, and signature Ben-Day dots transformed the look and language of postwar art. Born in New York in 1923, he studied at The Ohio State University before and after his WWII service, working closely with the influential teacher Hoyt L. Sherman. He later taught there and at SUNY Oswego, and from 1960 at Douglass College, Rutgers, where the ferment of Happenings and new media sharpened his turn to mass-culture imagery.

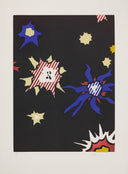

Lichtenstein’s breakthrough early-1960s paintings, appropriating comic strips and advertising, announced a cool, mechanical aesthetic that treated “high” art, commercial art, and art history with the same deadpan rigor. Museums quickly recognized the stakes of his project. Today, MoMA succinctly frames the throughline of his career as an inquiry into imitation itself, from comics to Cubism and classicism.

Major retrospectives have repeatedly recalibrated his legacy. The first comprehensive survey after his death opened at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2012 and traveled to the National Gallery of Art, Tate Modern, and the Centre Pompidou, underscoring the global reach of his achievement.

For a collector, it is important to understand that printmaking was not ancillary to Lichtenstein’s practice, it was central. The standard reference The Prints of Roy Lichtenstein: A Catalogue Raisonné 1948–1997 (Mary Lee Corlett; intro. Ruth E. Fine, National Gallery of Art) documents more than 350 graphic works across five decades, mapping how he used lithography, screenprint, etching, woodcut, embossing, and combinations thereof to refine ideas at scale and with exquisite control.

From the early 1960s he forged pivotal collaborations with America’s great print workshops, first with Tatyana Grosman’s ULAE on Long Island, a crucible for postwar print renaissance, and then with Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, whose master printers helped him push complex, multi-plate color structures and embossing. These partnerships gave his “machine-made” look its precise, artisanal reality.

A few landmark series illustrate the range and ambition of his editions:

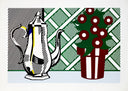

- Mirrors (1970–72): technically intricate prints that conjure reflections without depicting a subject, often combining lithography, screenprint, and embossing.

- Reflections, Nude, and Interiors (late 1980s–1990s): sophisticated, layered surfaces that simulate glare and glass while revisiting earlier Pop and art-historical themes.

- Haystacks (1969): One of Lichtenstein’s most conceptually audacious print series, Haystacks was his first collaboration with Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, produced between January and July 1969. The series comprises ten prints, including three state impressions derived from plates used in Haystack #6. Five of them are executed as lithographs with white screen-printed borders that amplify optical tension; one (the #7 in the series) is a relief print. Lichtenstein’s point of departure was the canonical Impressionist haystack cycle by Claude Monet, works that serially explored light, time of day, and atmospheric fluctuation. But rather than translate Monet’s painterly brushwork, Lichtenstein distilled the forms into networks of bold outlines and Ben-Day dot fields, reinterpreting the subject through his Pop lexicon.

Lichtenstein’s prints are of prime importance to collectors because of their parity with his paintings and their workshop pedigrees. Lichtenstein often debuted ideas in print or developed them in parallel, using the medium’s registration demands to sharpen graphic rhythm and color intervals. Leading museums exhibit these prints as primary works, not reproductive afterthoughts. Regarding the workshops where he produced them, imprints from ULAE and Gemini signal top-tier technique and historical importance. Both workshops are integral to postwar American print history.

Lichtenstein’s cool precision masks a deeply tactile craft: layered plates, calibrated screens, and embossments create surfaces that oscillate between printed flatness and sculptural relief. Museums such as MoMA and the NGA hold exemplary editions (including complete Mirror sets), underscoring their canonical status. For today’s collectors, these works offer the artist’s ideas at their most distilled, and with the benefit of rigorous workshop documentation and catalogue scholarship.